Great leaders don’t fail less than the rest of us. The truth is, they fail frequently, but successful leaders learn to see failure in a positive light.

Great leaders don’t fail less than the rest of us. The truth is, they fail frequently, but successful leaders learn to see failure in a positive light.

According to Patti Johnson, author of Make Waves: Be the One to Start Change at Work and in Life, setbacks are a signal to stop and take stock. Maybe it’s time to abandon this particular project and move on to the next thing. On the other hand, maybe this is the exact time to double your effort. No matter which route you choose, you first need to address your underlying emotions about whatever setback you’ve encountered.

Learn to Roll with the Punches

First, remind yourself that, from time to time, all leaders struggle with failed initiatives. Disappointment and other negative emotions are natural reactions.

For example, Johnson describes a feeling of disbelief hitting her team after a key sponsor said that the global change initiative the team had been working on needed a whole new outcome. The directive came “after months of work and a widely communicated launch date.” Johnson’s response to her team? Roll with it.

“I told them we had one night to be frustrated and angry,” she writes. “But the next morning all energies were to be spent on how we could adjust our plan.”

Focus on What You Can Control

Once you move past your initial disappointment, Johnson recommends focusing on what you can control. She cites Stephen Covey’s concept of the Circle of Concern (what we care about) and the Circle of Influence (what we can affect).

“The vast majority of people focus too much time and energy outside their Circle of Influence, in their Circle of Concern. Such people typically worry about things they can’t influence, much less control, such as the weather when they go on a beach vacation or who will become the new leader of their group.” The faster you can get to the “What can I do?” phase of dealing with setbacks, the faster you can start learning from the experience.

Learn from Your Leadership Setbacks

Johnson outlines the following self-assessment questions leaders can use to learn from setbacks.

- How credible was your vision or idea?

Whether you wanted to write a book, create a new department, or change a long-standing process, take a dispassionate look at how realistic your idea was. These questions will help you:

What gap or need did your idea fill?

What was the actual impact of your idea?

How much research did you do?

What facts guided you to the idea?

What experiments or tests did you perform?

Why did you believe the idea would work?

- Who were your stakeholders?

Were you able to generate enthusiasm and support for your idea from colleagues and decision makers? “This question is to determine if the idea was able to gain traction with others who want what you want,” writes Johnson. “Did you find interest in part of the idea but not all? What resonated and what didn’t? This question helps you determine if it is the idea that needs to be reconsidered, the way it was shared with others, or the execution.”

Again, disappointment is normal when you experience problems that get in the way of your vision. Be patient with yourself and remember that all your experiences, good and bad, can be viewed as growth steps.

“I’ve had many situations where my idea/plan/change didn’t quite gain traction at first, but I knew I was building support to benefit the cause for the next time,” writes Johnson. “Recognize your progress and decide how it can work for you in the future.”

What are your tips for leaders on how they can best respond to setbacks? Share your thoughts in the comments section.

[Image via Flickr / screenpunk]

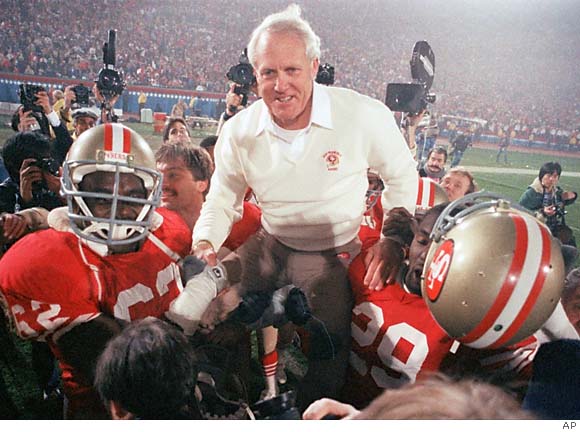

Find effective strategies. Vision is great, but if you cannot find a way to connect to it from the current reality, it’s useless. One leader who has been able to bring the imaginary to the realm of reality is football legend Bill Walsh. The legendary coach led his teams to amazing NFC division championships and NFC titles and earned a spot in the NFL Football Hall of Fame. One of his many strengths was as an offensive coach, constantly reading the field and creating strategies that would maximize his players’ skills and exploit the weaknesses of their opponents.

Find effective strategies. Vision is great, but if you cannot find a way to connect to it from the current reality, it’s useless. One leader who has been able to bring the imaginary to the realm of reality is football legend Bill Walsh. The legendary coach led his teams to amazing NFC division championships and NFC titles and earned a spot in the NFL Football Hall of Fame. One of his many strengths was as an offensive coach, constantly reading the field and creating strategies that would maximize his players’ skills and exploit the weaknesses of their opponents. Be a great communicator. The key to communicating is connecting with the audience. Former President Ronald Reagan was so well known for his ability to reach the American people that he earned the nickname, “The Great Communicator.” He didn’t use fancy language or rhetoric to win people over; in fact, it was the very simplicity of his style, coupled with his humor, which made him so popular. A senior leader’s job is to communicate corporate goals to employees and motivate them to achieve those goals.

Be a great communicator. The key to communicating is connecting with the audience. Former President Ronald Reagan was so well known for his ability to reach the American people that he earned the nickname, “The Great Communicator.” He didn’t use fancy language or rhetoric to win people over; in fact, it was the very simplicity of his style, coupled with his humor, which made him so popular. A senior leader’s job is to communicate corporate goals to employees and motivate them to achieve those goals. Listen. Sharing information is one skill; collecting information is another, equally valuable skill. And the queen of listening very well may be Meg Whitman, who is known for her humility and passion for listening to both her customers and employees.

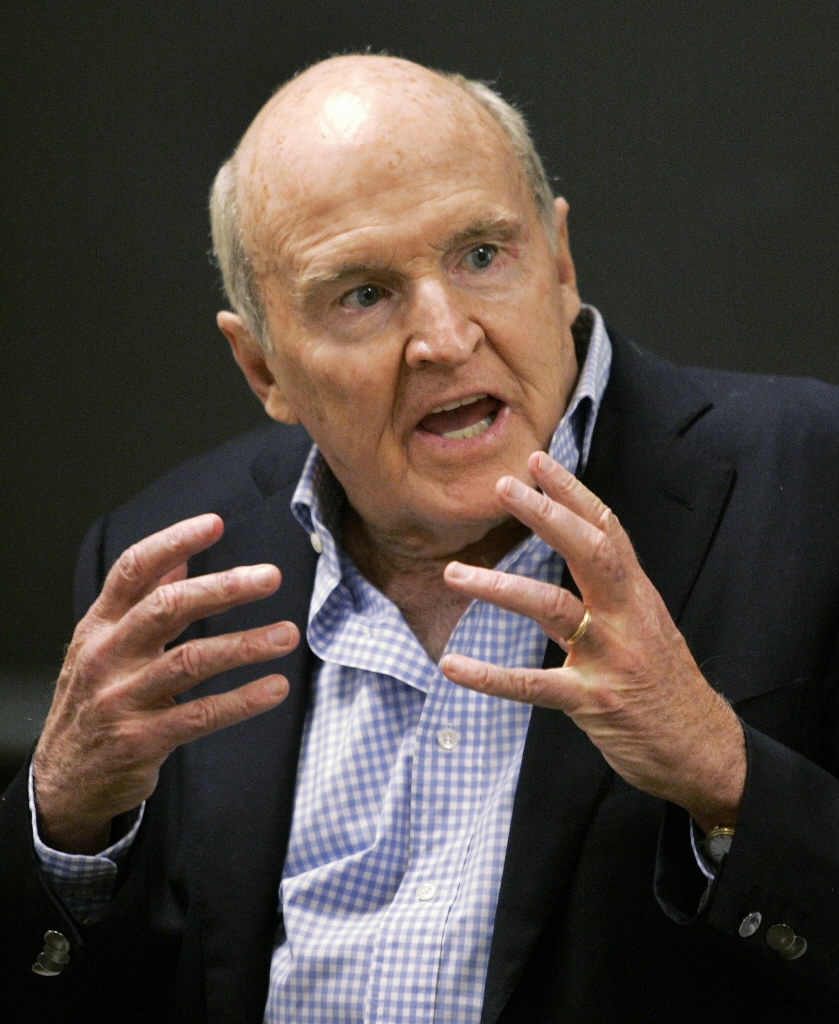

Listen. Sharing information is one skill; collecting information is another, equally valuable skill. And the queen of listening very well may be Meg Whitman, who is known for her humility and passion for listening to both her customers and employees. Be inspirational. If there is one skill that can make up for a multitude of sins in other areas, it just might be the ability to inspire. People want to be a part of something great, something larger than themselves. Just ask business legend, former General Electric CEO Jack Welch. Known for his passion, commitment, and sense of fun, Welch led by example and took pride in his ability to develop his people. He regularly rewarded the highest performers (and cut the bottom feeders), thereby encouraging workers to make it to the top. “Giving people self-confidence is by far the most important thing that I can do. Because then they will act,” Welch has said.

Be inspirational. If there is one skill that can make up for a multitude of sins in other areas, it just might be the ability to inspire. People want to be a part of something great, something larger than themselves. Just ask business legend, former General Electric CEO Jack Welch. Known for his passion, commitment, and sense of fun, Welch led by example and took pride in his ability to develop his people. He regularly rewarded the highest performers (and cut the bottom feeders), thereby encouraging workers to make it to the top. “Giving people self-confidence is by far the most important thing that I can do. Because then they will act,” Welch has said.

L.L. Bean was born in 1912, when Leon L. Bean (who was orphaned at age 12 and left school after completing the eighth grade) designed his own boot with a leather upper and rubber bottom. According to company legend, the first 90 shipments came back defective. Bean dispensed full refunds, borrowed $400, and launched a redesigned boot that became highly popular.

L.L. Bean was born in 1912, when Leon L. Bean (who was orphaned at age 12 and left school after completing the eighth grade) designed his own boot with a leather upper and rubber bottom. According to company legend, the first 90 shipments came back defective. Bean dispensed full refunds, borrowed $400, and launched a redesigned boot that became highly popular.

A lot of sales leaders let old myths about hiring get in the way of finding superstar candidates.

A lot of sales leaders let old myths about hiring get in the way of finding superstar candidates.